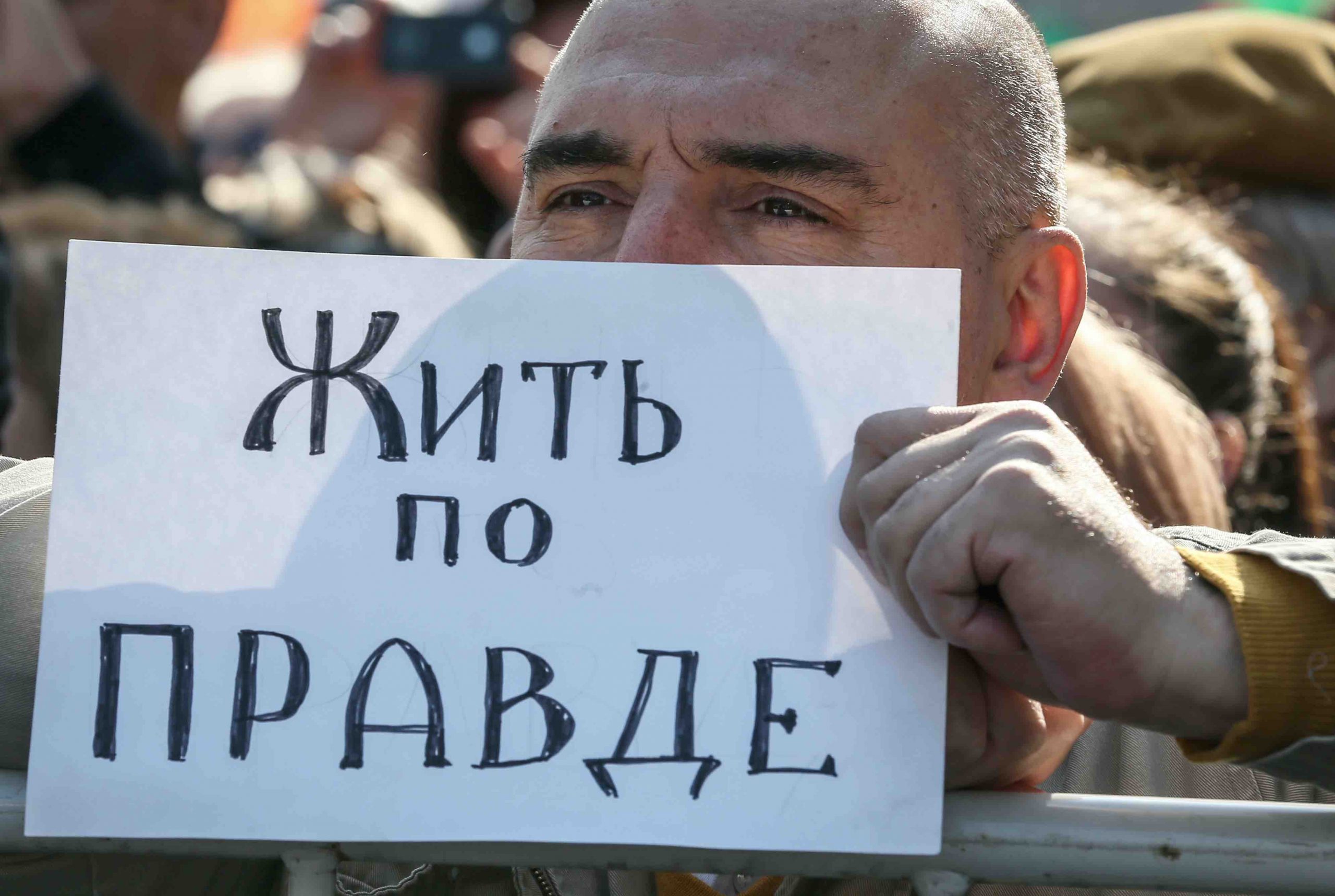

Ten years since the adoption of the law on foreign agents in the Russian Federation. IPI: “It was, and remains, a tool for arbitrary repression of independent media”

This month marks ten years since the adoption in the Russian Federation of the law on foreign agents, described by the International Press Institute (IPI) as “a key tool for repressing independent media.” According to the organization, this law, “long abused” by the Russian government, “was instrumental in causing self-censorship and a mass exodus of domestic and international outlets from Russia, as well as forcing the remaining independent media organizations underground.”

The source notes that, at the end of June 2022, a Russian public opinion research center published the results of a poll on the associations generated by the term “foreign agent” (a status applied to most independent media). Data show that 61% of respondents indicated that the term had negative connotations, while only 2% of citizens saw it in a positive light (11% found no association with the term, and 24% could not answer).

Among those who saw negative connotations, 14% of respondents associated it with the word “spy”, 7% with “traitor of Russia”, and 6% with the Stalin-era term “enemy of the people”.

Despite its origins, the poll reveals a key objective of the foreign agent label. “The law’s main aim is the same as when it was created: It is to silence civil society actors such as NGOs and members of the media and to make their life much more complicated”, said Daria Korolenko, a lawyer for the independent Russian human rights media project OVD-Info, in an interview with IPI. Ten years later, the aim of the law has not changed.

Evolution of the law

The IPI notes that the Kremlin’s fears of growing domestic dissent were the basis of the initiative and its continuity. “Its evolution both prior to and following the full-scale invasion of Ukraine provides a timeline for the growing censorship and curtailment of press freedom that accompanied the increasingly aggressive stance of the Kremlin regime, both at home and abroad,” IPI writes. “Internal repressions occurred in parallel with preparations for external aggression,” said Aleksei Obuhov, editor of the SOTA outlet.

According to OVD-Info, 170 organizations were labeled as foreign agents between 2012 and 2016.

By 2017, amid protests organized by opposition politician Alexei Navalny, the law was expanded to include news outlets, which, once on the list, became subject to financial pressure and legal scrutiny. Thus, in addition to the obligation to submit quarterly financial reports, the foreign agent label led to curtailed cooperation with government institutions, civil society organizations, and others who feared being associated with this label.

At first, the law targeted foreign media outlets that were funded by foreign governments, such as RFE/RL, and later extended to all independent media outlets in general, including domestic ones. The IPI points out that going on a press tour or an international conference paid for by a foreign organization, or even receiving money from a relative or friend abroad, was enough to be declared a foreign agent.

At the end of 2019, the introduction of amendments to the law allowed individuals to be included in the list of media organizations acting as foreign agents, too. “The foreign agent law was not about regulating foreign funding – it was, and remains, a tool for arbitrary repression of independent media,” notes the text published by IPI.

By the end of 2021, about 1,500 activists and journalists had been forced to flee the country. Over 100 legal entities and individuals had been designated as media organizations acting as foreign agents. Those remaining were often forced to engage in self-censorship simply to continue their operations. Igor Dodon commented for Sputnik Moldova on the response of the ISS to Media Azi: “They [ISS] refer to a government decision from 1995. That decision says that accreditation for foreign journalists is required for two years with state institutions. Otherwise, we are a free country and any journalist can come and interview whoever they want